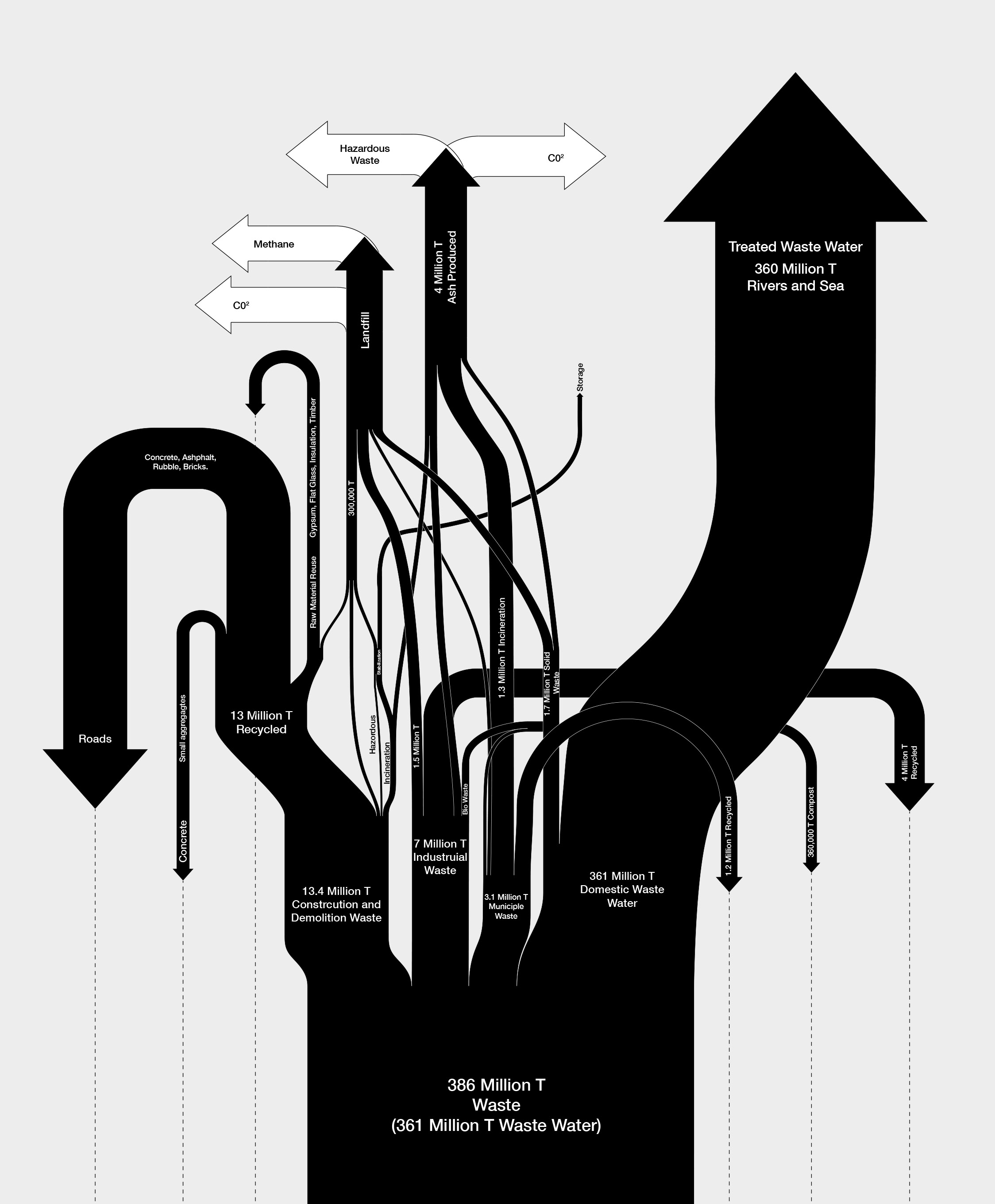

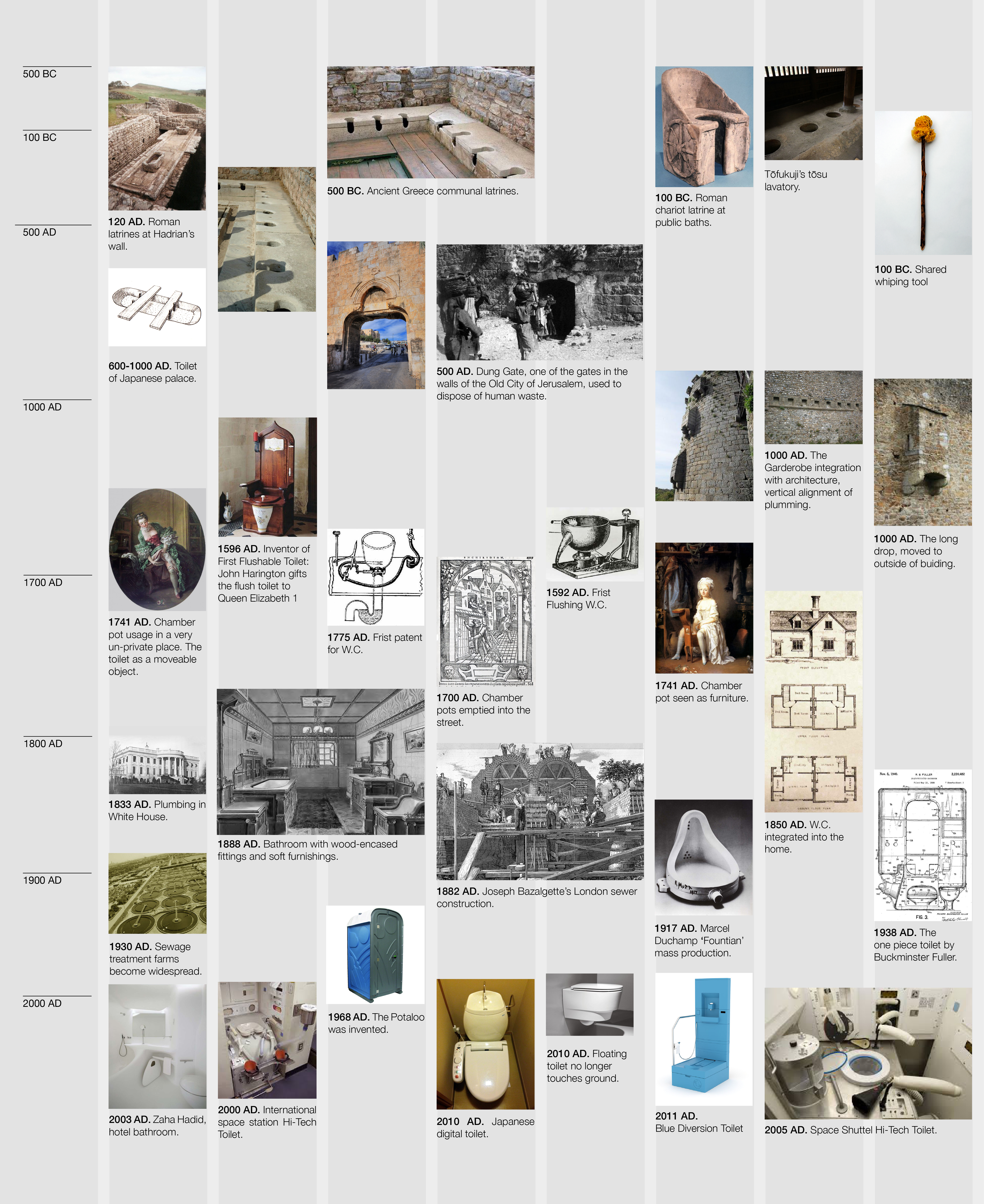

The move away from the collective is illustrated by the changing relationship with (human) waste. The individual forgets that consumption, which has become a predominant element of all our lives, results in waste. Brought on by the introduction of municipal sanitisation and the flushing toilet was the idea that waste can be moved into unconsciousness resulting in today’s ‘flush and forget’ culture where waste is disposed of, for someone else to deal with. Serviced by an invisible infrastructure beneath the ground.

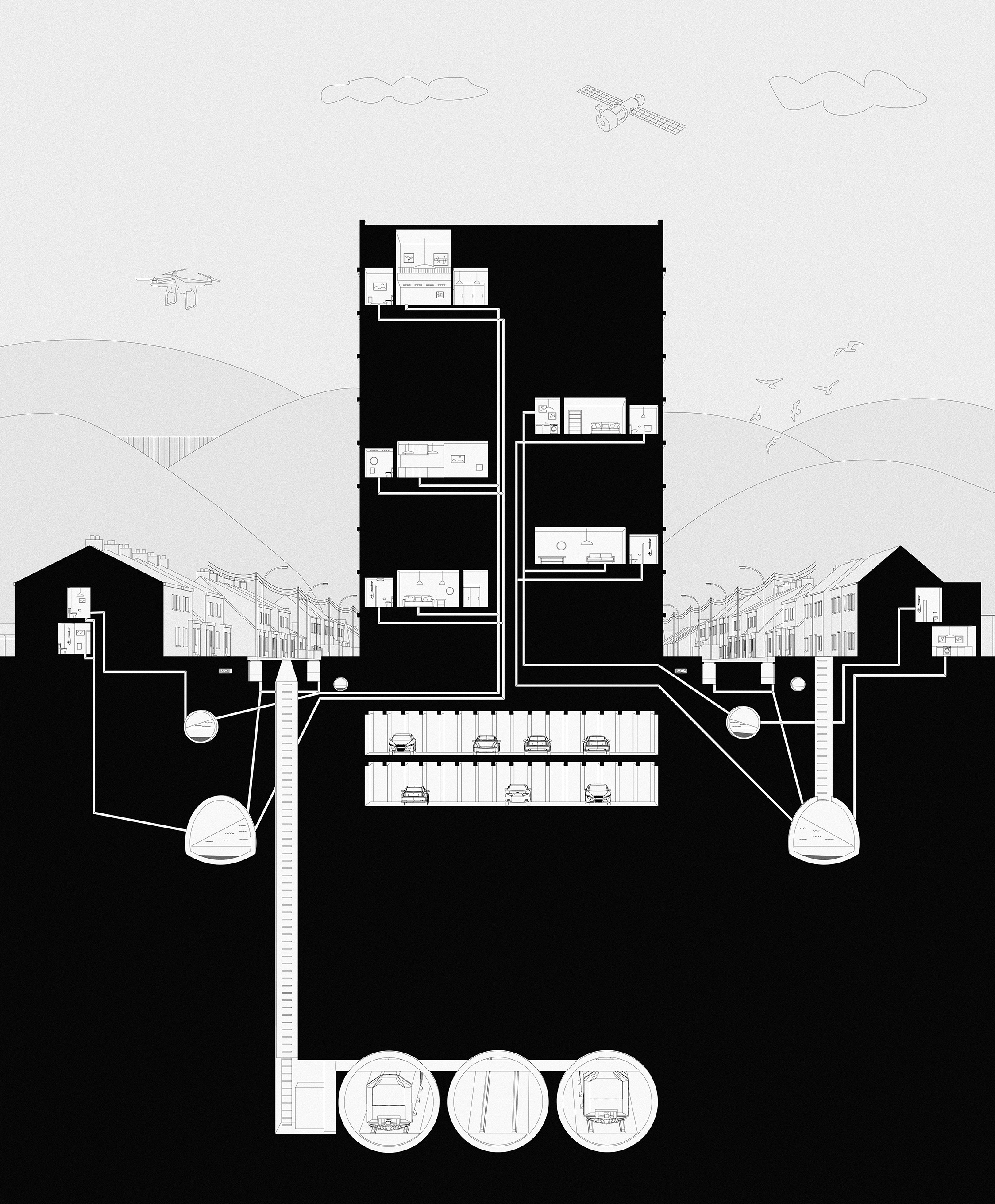

The sewers are the backbone of the modern city. They are inexorably connected to urbanisation, sprawl, and consumption. With the introduction of this subterranean urban landscape, connections between distant sources of water in remote areas and the metropolis completely changed our concepts of space and time, expanding the city’s limits infinitely underground and thus permanently modifying the landscape. We now deal with

The sewers are the backbone of the modern city. They are inexorably connected to urbanisation, sprawl, and consumption. With the introduction of this subterranean urban landscape, connections between distant sources of water in remote areas and the metropolis completely changed our concepts of space and time, expanding the city’s limits infinitely underground and thus permanently modifying the landscape. We now deal with

our waste in the style of a chemical plant located in an industrial estate outside the city, taking all emotion and physical involvement away from the subject. It is no longer visible in our day to day lives and is now encased in anonymous architecture, hidden away from public view, and no longer celebrates the process of extracting its value.

Before the 1840s with the introduction of Bazalgette’s sewers in London, human excrement had not been regarded as ‘waste’. It was part of the working agrarian economy, the workers of the land brought their livestock or harvests to sell in the city, then collected the ‘night soil’ from the city’s streets to transport back to the field and use it as fertiliser. This system was broken with the development of sanitary infrastructure and in the process, the boundary between human activity and natural processes becoming fractured.

Before the 1840s with the introduction of Bazalgette’s sewers in London, human excrement had not been regarded as ‘waste’. It was part of the working agrarian economy, the workers of the land brought their livestock or harvests to sell in the city, then collected the ‘night soil’ from the city’s streets to transport back to the field and use it as fertiliser. This system was broken with the development of sanitary infrastructure and in the process, the boundary between human activity and natural processes becoming fractured.